The systems of decision-making in most mixed economies vary depending on the sector and the shortcomings of the market in meeting the societal demands of certain goods or services. While examining some of these models, I found that they often rely on very simplistic models of consumers, and wondered how some of the more nuanced, complex aspects of consumer behaviour could manifest on a greater scale.

I looked no further than the deregulation of the energy market in Victoria.

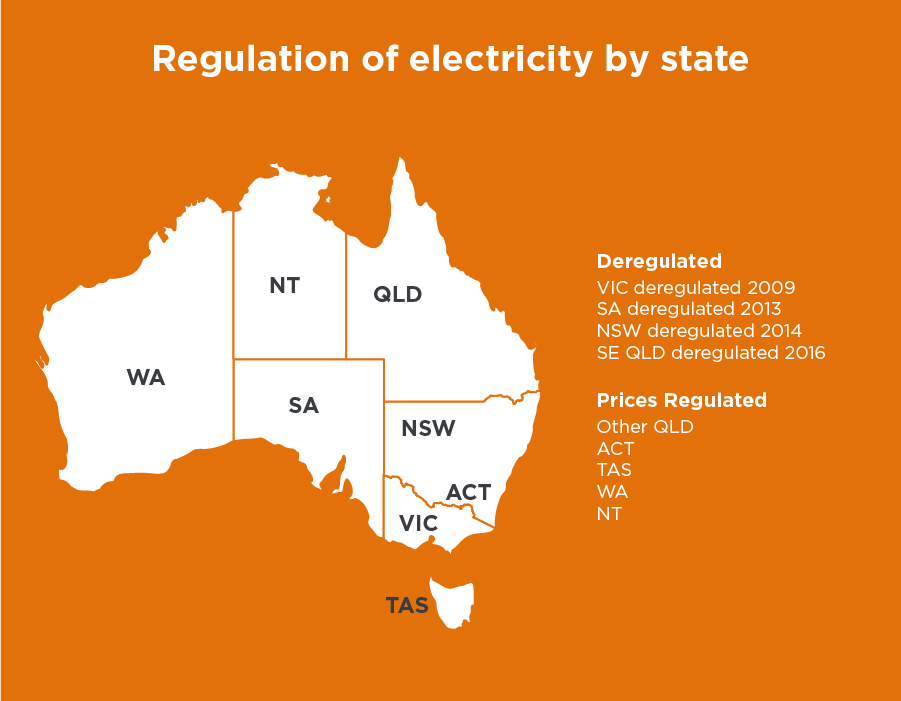

In 2009, Victoria (followed by New South Wales, Queensland, and South Australia) completely deregulated competition and prices in the energy sector, with the intent of “allowing [customers] to choose which company suits them best… and stimulating competition between energy companies”. Traditional economic models support this decision.

The 19th Century economic theory of laissez-faire market capitalism states that the deregulation of the energy sector would incentivise more efficient production, and as companies “compete for market share, they are incentivised to offer lower prices, and better services”.

So how did Victorian energy producers and consumers react?

To put it simply. Victorians ended up paying MORE for energy than they had been initially.

On average, Victorian consumers were paying 21% ($294) more than the cheapest option available on the market. Only a small group of consumers achieved the cheapest offers, and these were the “well-informed consumers that regularly switched providers”. This effect contradicts the ‘homo-economicus’ (‘rational consumer’ model), in that consumers have bounded rationality and their weighing of options based on maximising utility is compromised by internal and external factors.

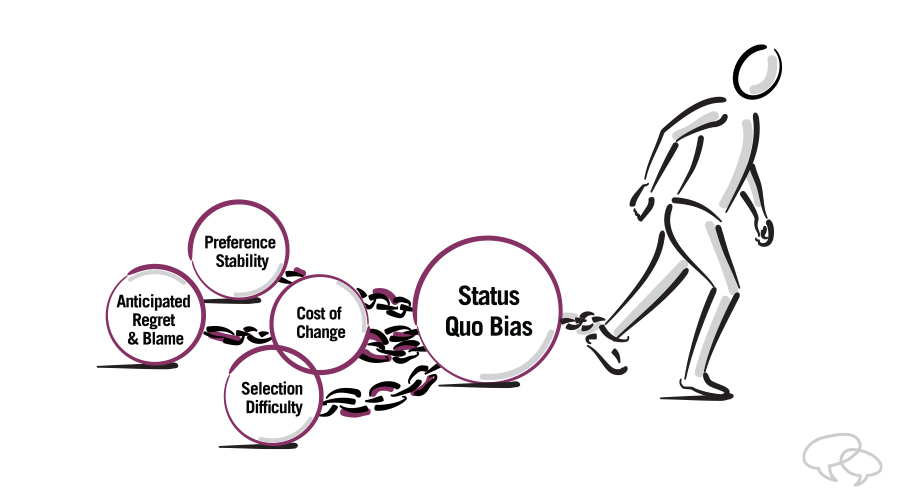

One such factor is the status-quo bias, the ‘cognitive inertia’ that drives consumers toward the status-quo alternative (i.e. staying with the current decision) in an economic decision (or any decision for that matter). This psychological phenomenon integrates into this economic issue, as Victorian consumers too, have a tendency to stay with their current energy providers (the status-quo alternative), despite this not being in their best interests.

“To do nothing is within the power of all men” – Samuel Johnson

Samuelson and Zeckhauser, 1988

A secondary factor affecting this struggling policy is the disproportional impact (or ‘vividness’) of personal human interaction over impersonal (and usually, more reliable) studies. The deregulation of competition forced emerging and established energy providers to invest in marketing strategies (also increasing retail costs, making up around 30% of a typic energy bill), and more specifically, door-to-door sales. 55% of total residential sales in the energy sector were made through the door-to-door channel, and 60% of energy providers deemed the door-knocking channel as a ‘very important’ sales channel. Face-to-face sales pitches, that involve human interaction seem to sway customers toward an energy provider that may not necessarily be their best choice.

The above factors are complemented by the time-constraints faced by customers when making economic decisions (such as picking an energy provider). In today’s fast-moving economy, it is often difficult to examine the rates and services of each energy provider and rank them in order of increasing utility. As a result, consumers stick with their current providers, or switch providers because a salesperson ‘made them an offer they can’t refuse‘.

Now, while it is absurd to conclude that the human mind and its implicit biases are the primary cause of this failing policy (that has caused a 114% increase in energy costs over the last decade), it is worthwhile examining the internal biases and the more obscure factors that limit our (the average consumer’s) rationality. It cannot be concluded that consumer behaviour was the sole reason for this policy’s failure, but it can be hypothesised that bounded consumer rationality is a vital factor that must be accounted for when implementing any economic policy.

Will the re-regulation of the energy-sector benefit consumers? How will the legislation against door-knockers affect sales for energy providers? How the increasing importance of environmental sustainability exacerbate the issue of rising energy prices? Can there be too much competition in a given sector?

With Australia’s chances of heading into recession increasing by the hour, these are all to which questions we must find the answers, or else we might find ourselves living in the dark.

Some other perspectives on this topic

- Slocum, T (2007) The Failure of Electricity Deregulation: History, Status and Needed Reforms, Public Citizen’s Energy Program. viewed 06 March 2020, < https://www.ftc.gov/sites/default/files/documents/public_events/Energy%20Markets%20in%20the%2021st%20Century:%20Competition%20Policy%20in%20Perspective/slocum_dereg.pdf >

- Shim D, Wan Kim S & Altmann, J (2017) ‘Strategic Management of Residential Electric Services in the Competitive Market: Demand-oriented Perspective – Energy & Environment.‘ viewed 06 March 2020, < https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0958305X1 7740234?icid=int.sj-abstract.similar-articles.2 >

nice! 😎😎

LikeLike

it seems like consumers aren’t acting in their own interest… It is really interesting how people never change their energy provider, and I have certainly seen my parents do so. Interesting conversation and a great blog.

LikeLike

A really interesting issue. It’d be fascinating to see the impacts of this economic behaviour in areas outside of the energy market and how this can be applied to policy making in future.

LikeLike