Ideally for governments (democratic or otherwise), the majority of people in a society should be constantly working and contributing, paying income taxes and other fees in the process to the government, which then decide where that money will be allocated. In Australia, our government use that income to provide services such as healthcare, education, defence, infrastructure et cetera. However, as life expectancy continue to steadily rise and birth-rates continue to decline, Australia among many other countries are heading into a unique challenge that they are facing for the very first time, how to deal with an Aging Population.

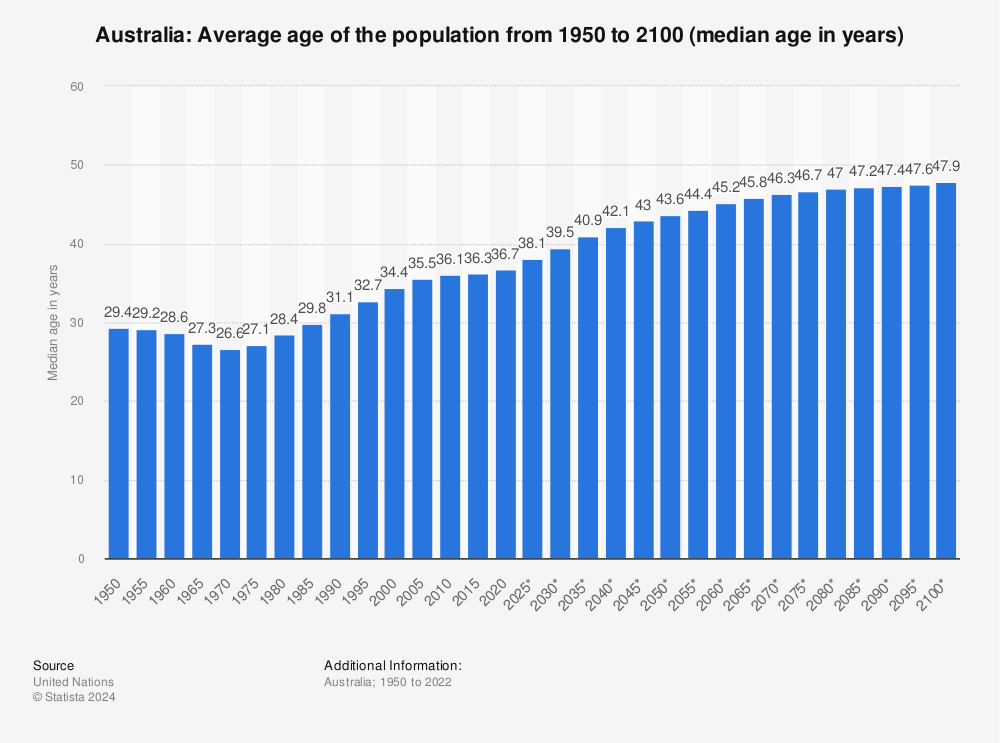

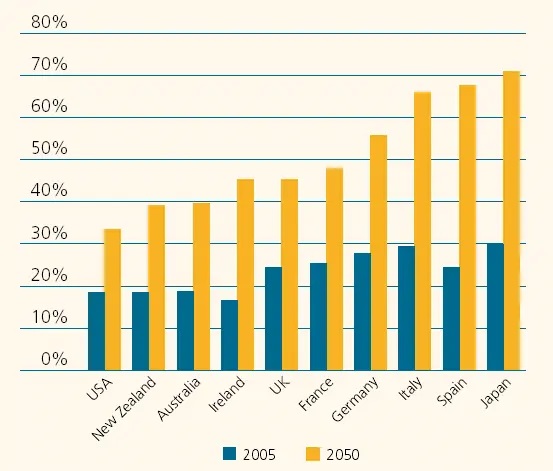

Experts estimate that by 2050, older people will outnumber young adults and adolescents for the very first time in human history. Australia’s current population stands at 25 million at the time of writing, the latest projections suggest it will increase to around 50 million by 2100. The steady growth in the population hides the potential issue of an increasing median age, currently at 37 years, it is expected to increase to 42 years shortly after 2050. All governments in the world are founded and designed on the optimistic assumption (status quo bias) that the population will be in constant and steady growth, it is a system that entirely relies on the idea that workers who choose to retire will immediately be replaced by new and young workers, who then pay for the retirement benefits of the former. An increasing ratio of elderly to working age (Age Dependency Ratio) will cause major changes to governments, societies and both macro and micro economics.

The Economic Effects of an Aging Population:

Society and government:

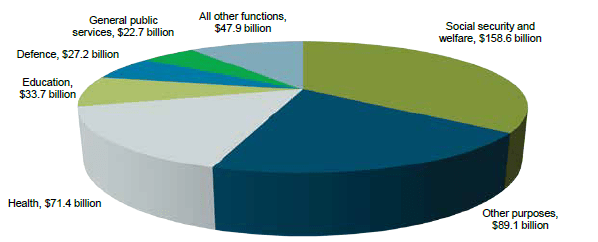

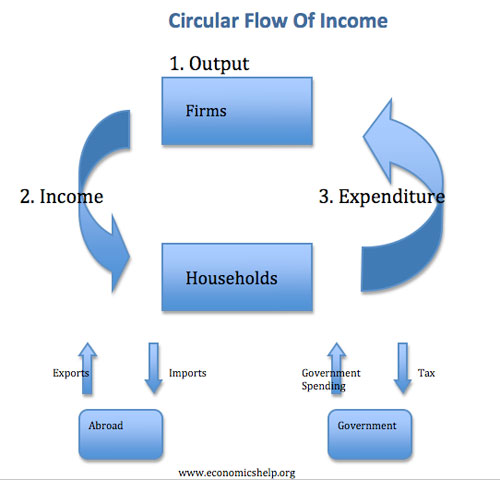

As population ages, more people are retiring from the workforce and not enough entrants are replacing them. This places a massive burden on the government and society. The government will have to adjust the budget (right image) in relation to the demographic shift and account for the increase in age pension and healthcare. A country with an aging population is also likely to experience lower levels of economic growth, as people are more likely to save for retirement instead of spending their income, generating lower economic activity in the process. Inflation rates are also likely to lower as a result of less spending and overall demand.

When governments raise the taxes to counter the costs of an aging population, it will have a profound impact on the entire economy, as individuals and companies are forced to scale back investments and spending, resulting in decreased activity in the circular flow of income.

Employers:

A high age dependency ratio will lead to the shortage of new workers in the workforce, leading businesses to offer better wages and more flexible working practises to attract workers, there will be less competition in the workforce as a result. As most elderly are less willing to spend, the equilibrium price will also drop to meet the new decreased demand. The combination of the two factors will lead to a drop in productivity to match the lowered demand caused by negative population growth.

Employees:

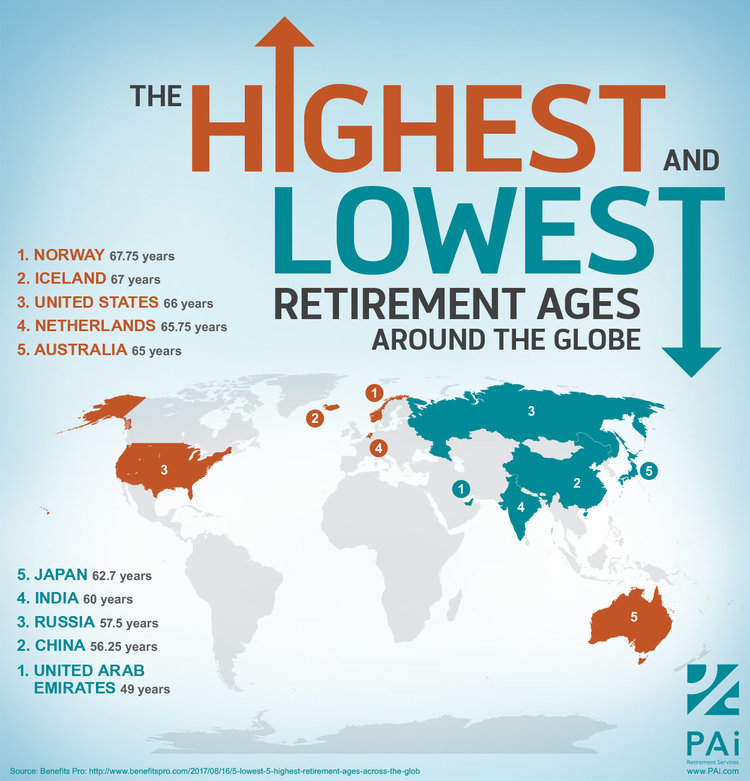

The working population will likely have to pay higher income tax as a result of the rising dependency ratio. More workers could also work in the aged care and health sectors as a result of an increasing demand created by the increasing number of elderly. Workers are likely to be better qualified and trained as the workforce shrinks. Governments are also likely to raise the retirement age to lower the pressure on age pension and healthcare, if Australia’s median age continue to rise like projected, it will mean future workers would have to retire considerably later in life to receive age pension.

How Australia and other countries can deal with the issue:

One way of dealing with the issue is by introducing or raising the pension fund. The Commonwealth Government of Australia introduced superannuation guarantee (SG) in 1991 to counter the aging population. The SG works by taking a portion (currently 9.5%) of a worker’s income and putting it into a super fund, the fund is inaccessible by the individual until they retire and no longer receive an income. The purpose behind the SG is to force all workers to save to relieve pressure on Australia’s age pension when they retire. However, it will not have much of an impact on people retiring in the near future, as it is introduced too close to their retirement for meaningful amount of money to be saved up (superannuation wasn’t compulsory prior 1991). The Superannuation fund is also heavily invested in the stock market, which is currently suffering its worst drop since the Global Financial Crisis due to the looming recession. As a result of the above factors, many current and near-future retirees will not have enough savings to see them through retirement.

A country can also deal with this issue by raising the retirement age (more subtle way of saying make people work longer). As the average life expectancy increases, most workers will be able to work past the current 65 retirement age. Australia have already raised the retirement age by 6 months every 2 years until it reaches 67 by the third quarter 2023. However, some people will experience health problems that prevent them from working to the delayed retirement age, raising the figure will also cause discontent among the working population.

To account for the growing age dependency ratio and the rising age pension and healthcare costs that comes with it, a country is likely to raise the income tax for working individuals as well as corporal taxes. In 2019, the two taxes accounted for more than 65% of the total revenue of the Australia government. Raising the two will raise considerably more funds for the government that can offset the increasing costs of pension and healthcare. However, raising income taxes will encourage individuals and businesses to save up rather than to invest, further damaging the economy.

Rather than increasing the productivity or raising the retirement age to offset the costs of an aging population. Governments can also use policies to boost the size of the workforce. Opening up to immigration is an effective solution to an aging population, as most migrants are of working age and they often bring wealth with them to spend and invest. However, many oppose to the solution as immigration also tend to drive down wages and place stress on inner-city housing.

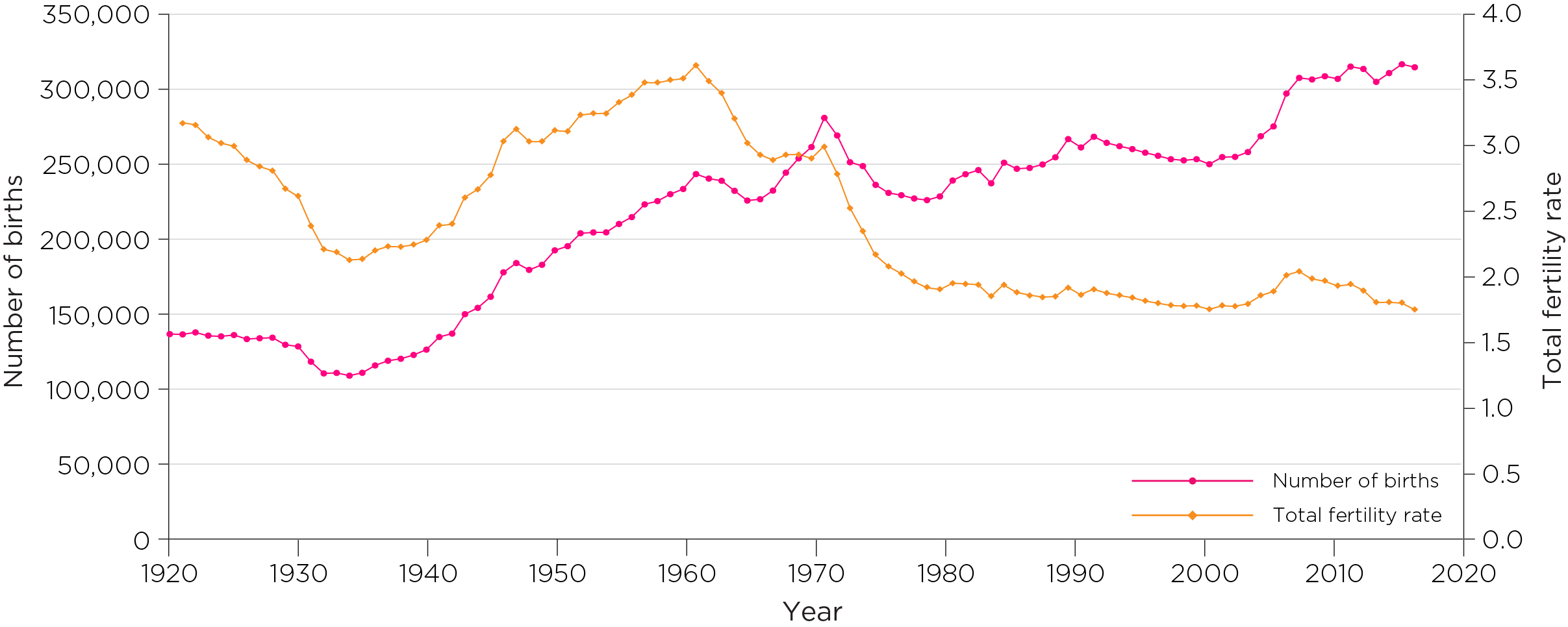

A long-term solution is for governments to offer incentives to their citizens to raise the birth-rate high enough to counter the aging population. Australia’s birth-rate is currently around 1.7 and has not reached the replacement rate (at least 2.1 children per woman is required for sustaining population levels) since 1975, it is difficult to see any policy to be effective in raising that figure, as other countries such as Japan and many European countries have tried to offer tax breaks as well as payments with little effects.

https://virginmoney.com.au/superannuation/understanding-super/how-does-super-work-in-Australia

http://www.apimagazine.com.au/property-investment/3882

https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/0/1CD2B1952AFC5E7ACA257298000F2E76?OpenDocument

https://www.economicshelp.org/blog/8950/society/impact-ageing-population-economy/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pension_fund

https://www.servicesaustralia.gov.au/individuals/services/centrelink/age-pension/who-can-get-it

https://treasury.gov.au/review/tax-white-paper/at-a-glance

https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-51118616

https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.DYN.TFRT.IN?locations=AU

https://www.taxsuperandyou.gov.au/node/131/take

https://aifs.gov.au/facts-and-figures/births-australia/births-australia-source-data

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/2158244017736094

https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2019/10/ageing-economics-population-health/