As the COVID-19 pandemic continues to wage its war on health, governments across the globe have been forced to adopt additional economic policy such as expansionary monetary policy, in a bid to prop up a struggling global economy. The Australian government is no exception, working with the RBA to slash interest rates to all-time lows, in a bid to encourage consumer and business spending to keep the economy afloat during this health crisis. Despite these measures, the Melbourne Institute and Westpac Bank Consumer Sentiment Index reached an all-time 30 year low since 1991, of 75.6 points in April and barely stabilising to 79.5 points in August.

With Australia now almost certainly heading into our first recession since the ‘90s, the debate surrounding the effectiveness of current monetary policy is flooding the headlines of Australian media. Throughout this debate, discussions by politicians, institutional leaders and informed Australians surrounding the efficacy of negative interest rates as a tool of monetary policy, to encourage economic growth have emerged. Despite the historically-low cash rate of 0.25%, there are still concerns that this is not enough to adequately stimulate the economy, with some of the nation’s most senior economists such as Bill Evans (the chief economist at Westpac bank) urging the RBA to take interest rates to negative territory.

But what exactly are negative interest rates?

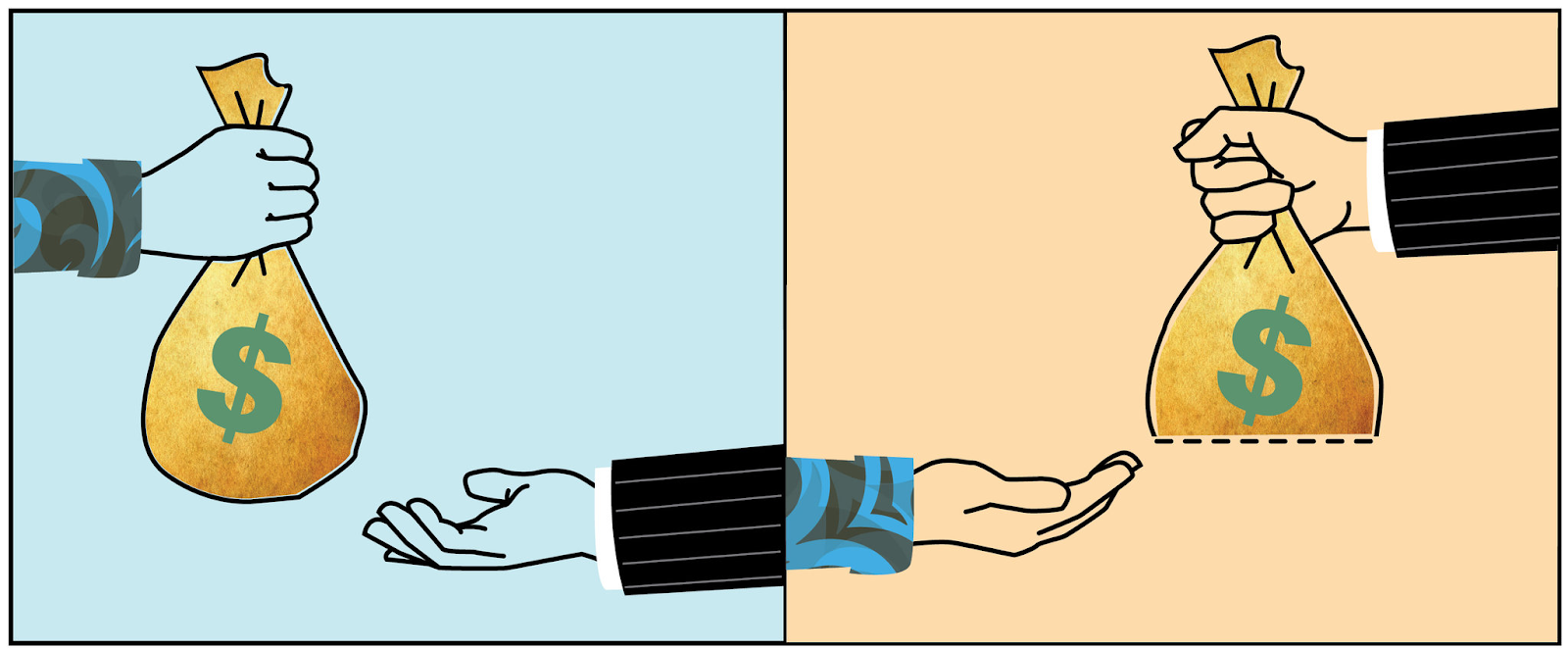

Interest rates can be defined as charges by a lender for the use of certain assets, usually expressed in a percentage of the principal amount. Put simply, they are the cost of borrowing something from someone else with the agreement that whatever is borrowed is returned fully later on. These are most applicable in the context of the bank. When depositing money into a bank, the depositor acts as the “lender”, with the bank paying the individual interest to keep their money stored there. Conversely, when the bank provides a loan they act as the lender, the recipient of the loan paying the bank in the form of interest for the use of the money from the loan. The idea of interest rates is that they provide a borrower with a certain amount of safety and security around the asset they have lent.

Negative interest rates flip this lender-borrower system on its head. Rather than paying banks for holding on to its customer’s assets, the Central Financial Institutions (equivalents of the CBA) instead charge these banks for holding deposits. As such, subsidiary banks charge less (or even pay) for their customers to take out loans. Whilst seemingly amazing on the surface (who doesn’t want to be paid to take out a home loan), what do these rates actually mean for the economy and how effective have they been in the real world?

Negative interest rates have been undertaken by several central banks in both Europe (the Danemark (Denmark’s) National Bank, the European Central Bank, the Swiss National Bank) as well as in the Bank of Japan. They were introduced by these advanced economies in order to combat the consistently low inflation rates that these countries experienced and avoid their tumbling down a spiral of deflation and negative economic growth – an unconventional form of expansionary monetary policy.

In theory, since negative interest rates have the basic intended effect of discouraging saving and incentivising borrowing, spending and investing, they should lead to an increase in both consumer and investor spending (thereby increasing aggregate demand); stimulating both inflation and economic growth. In addition, negative interest rates would theoretically lead to a depreciation in the economy’s currency, as the reduction in returns would decrease foreign investment, thereby increasing the competitiveness of the nation on the export market – another injection to aggregate demand.

However, the implementation of negative interest rates has many unintended, and sometimes counterintuitive effects on consumer and institutional behaviour, and therefore the aggregate economy.

The ability of banks to earn profit is severely hindered by negative interest rates. Ever since the Eurozone first implemented negative rates in 2014 (currently -0.5%), the profit-earning ability of European Banks (60% of which comes from net Interest Income) has been severely hindered, leading to a 50% reduction in the EuroStoxx Bank Index. This strain on banks is paralleled in the Japanese economy, where Japan’s largest private bank (Bank of Tokyo-Mitsubishi UFJ Ltd) announced in 2016 that they wished to leave the Japanese bond markets because negative interest rates had made them unstable.

Consumer behaviour has not necessarily responded to negative interest as models would expect. A report from the Wall Street Journal finds that customers in Europe have responded to negative interest rates by moving their savings around banks offering higher yields, and high-volume depositors are requesting that their physical cash be stored in vaults where negative interest rates can be avoided. This behaviour has caused inflation in Europe to remain at a lacklustre 0.4%.

A move to negative interest rates may actually incentivise consumers to save more due to their damaged outlook of the economy. In other words, a move to negative rates may signal to consumers that the economy is weak, and cause them to be more cautious with their savings, a paradoxical outcome that has unfortunately been experienced in German households, which experienced a 1.1% increase in net savings rate from 2014 to 2019.

Both the European Central Bank and the Bank of Japan have implemented negative rates to fight deflation, but have not been able to move rates back into positive territory since they were first implemented (in 2014 and 2016 respectively). This is due to the previously stated factors as well as the side-effects of an aging demographic faced by both economies.

So, considering the application of negative interest rates across the globe, how viable are they in Australia? With economic authorities such as Reserve Bank Governor Phillip Lowe stating that it is “extraordinarily unlikely” that Australia will pursue negative interest rates during COVID-19, the simple answer is no. But why exactly is this the case?

The main benefit of implementing negative interest rates is that they cause a downward pressure on the exchange rate for Australian currency. As banks no longer offer a favourable return on investing in Australian dollars, foreign investors are no longer incentivised to invest in it, decreasing demand for the currency. As demand decreases, the currency depreciates which is beneficial for the Australian economy, as it makes the country’s exports more internationally competitive. The increase in exports results in increased aggregate demand, thus creating increased economic growth.

Despite these benefits, negative interest rates have the potential to be significantly detrimental for the economy. This is particularly in regards to the financial system and consumer psychology. The implementation of negative interest rates considerably hinders banks’ abilities to earn profit and provide loans, reducing consumer and business spending and in terms of consumer psychology, can promote additional saving rather than spending.

These negative consequences have both been experienced by the Japanese and European economies, who are yet to reap the intended benefits of this unorthodox monetary policy. With these two consequences, negative interest rates are unlikely to have their intended effect on the economy, hindering rather than promoting economic growth.

Considering the significant potential detrimental effects of negative interest rates on the economy that far outweigh the benefits, it is highly unlikely that they will be viable in Australia. With the economy still reeling from the effects of flash flooding, unforgiving bushfires and a global pandemic that has yet to subside, the implementation of an experimental form of monetary policy is the last thing the country needs.

In saying this, while the economies that have already administered negative interest rates have yet to experience their quoted benefits, it is far too early to write them off as “bad policy” (the global pandemic is not helping their cause either). The net effect of negative interest rates on modern economies is ultimately an empirical question , and only time will tell whether this monetary policy is a trapdoor toward an economic downturn or a saviour for lacklustre economies.

Reflection (Richard and Pranit):

Our goal for this Macro-Economics project was to delve deeper into monetary policy and push the boundaries of our understanding on how manipulating interest rates can have a profound effect on the aggregate economy.

Our approach to this research and presentation task was quite methodological, with broad and deep research being the first step, and then the drafting stage preceding the creation of the final article. As such, we have come out of this project more informed on the intentions and current effects of negative interest rates in the countries in which they have been implemented and have been enlightened to the different flow-on effects that any monetary policy may have on the aggregate economy.

In terms of the article, we believe it was thorough and well referenced. It was aimed at clearing up the doubts and misconceptions that have arisen due to discussions on negative interest rates in the political community, which was done through examining the implications of this policy in great detail. If we were to improve the article, we would have been more concise with some of our explanations and perhaps narrowed our perspective onto a more specific sub-topic. In saying that, we are both satisfied with our final article and we hope that the people who have read it learn something new!