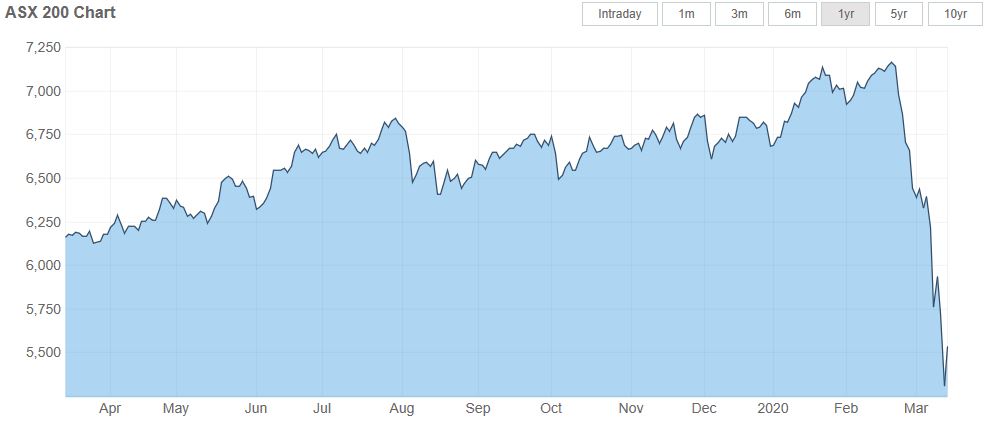

COVID-19 has wreaked havoc across the world, with large countries such as Italy and China in full or partial lockdown to stop the spread of the virus. Stock markets around the world have also taken a tumble, with Australia’s ASX 200 losing over 22% of its value in less than a month. It appears to be only a matter of time before Australia goes into some form of lockdown, and this has caused widespread panic amongst consumers. Australians buying excessive amounts of toilet paper has made worldwide headlines due to the absurdity of toilet paper being hoarded instead of food or other necessities. What makes it more illogical is that toilet paper is produced locally and its supply is unaffected by COVID-19. This is an example of herd behaviour, which is a recurring factor in a financial crisis.

Herd Behaviour: Individuals making decisions according to what others are doing, despite this not being the decision they would make alone.

The economic uncertainty displayed by consumers amid COVID-19 is similar to the consumer behaviour exhibited during the GFC that took place between 2007 and 2009. The Australian government recently unveiled a $17.6billion stimulus to boost the slowing economy, which includes $750 payments to some of the lowest income Australians and financial assistance for small businesses. Comparisons have been drawn between this stimulus and the stimuli provided by the Rudd government in October 2008 and February 2009, with the second stimulus being particularly similar in nature to the Morrison COVID-19 stimulus. The GFC, however, is not COVID-19. The two situations are vastly unalike, and similar stimulus packages to combat each problem will likely have dissimilar outcomes as various circumstances are different.

The GFC

The Global Financial Crisis (GFC) was a period of extreme economic stress and instability around the world. The GFC was caused by behaviours stemming from high consumer confidence in America such as extreme borrowing and risk taking in American markets, which led to the ‘bursting’ of the American housing bubble. These events alone decimated consumer confidence, however this was amplified by the collapse of the fourth largest investment bank in America, Lehman Brothers, in September 2008. In a panic, many investors sold their shares to avoid the uncertainty that would follow, causing the market to plummet further. The result was the creation of a dysfunctional market with nobody willing to buy shares, even at substantially lower prices.

With the world’s largest economy in turmoil, many other countries suffered similar consequences as the US and went into recessions. This is due to the interconnectedness of the world’s economies, and is explained in the video below.

Australia’s Response

Australia was one of the very few economies that avoided a recession, and did so due to policy and circumstance. Following the collapse of Lehman Brothers, the Australian government released its first stimulus worth $10billion in October 2008, which focused on assisting pensioners and lower income families with the fallout of the economic downturn, as well as encouraging first homebuyers with an increase in the first homebuyer grant.

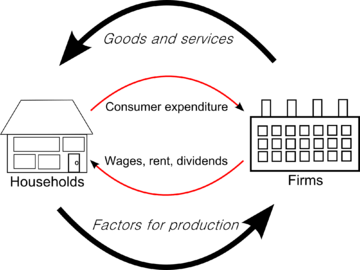

This was followed up with a second stimulus worth $42billion in February 2009, which aimed to encourage spending and secure jobs. The stimulus was headlined by $950 cash payments to people earning under $80,000 annually, as well as smaller payments for others earning between $80,000 and $100,000. This was an attempt to counter the decrease in consumer confidence by encouraging spending. An increase in spending increases profit made by businesses, allowing them to produce more goods and services for the economy, so consumers can buy them and the cycle continues. This is called the circular flow of income, and its fluency is crucial for a functioning economy.

The GFC is an example of what happens when a breakdown of the circular flow of income occurs, as consumers spent less meaning businesses needed to lay off staff to cover losses. This lowers consumer confidence, which in turn causes them to spend less, and again the cycle continues. This relates to another part of the February 2009 stimulus, with over $20billion being contributed towards upgrading schools, infrastructure and housing, in an attempt to create jobs and control unemployment.

The COVID-19 Stimulus

Similar to the Rudd government’s second stimulus, the Morrison government’s stimulus contains a $750 payment to lower income Australians which encourages spending. The reasoning for the payments from both stimuli to be targeted towards lower income Australians is that they have to spend it on essentials, increasing circular flow, whereas many middle or high income earners would elect to save the money, which doesn’t assist the economy.

$6.7billion is being spent on funding employee wages and salaries of small businesses, aiming to ensure people don’t lose their jobs due to decreased spending by consumers. A further $3.9billion is being contributed to incentives encouraging businesses to spend more, with the goal of increasing consumption.

Evaluating the success of the GFC stimuli

At first glance, it appears that the stimuli implemented by the Rudd government during the GFC were successful as Australia avoided a recession. This may be true, or at least partially true, however there were also some favourable circumstances that assisted Australia’s economy.

After an initial economic decline during the GFC, China quickly bounced back due to its prospering economy. China’s demand for Australian goods and services (and vice-versa) allowed for importing and exporting to continue and helped boost the economies of both economies. Having China as Australia’s biggest trading partner greatly assisted Australia during the GFC, and it could have been a different story had Australia’s not had a strong economy like China to rely on.

Australia was also assisted by a strong economy of its own. Prior to the GFC there was no government debt, which allowed for such large stimuli to be implemented. The stimuli were scrutinised while the country was in a strong position financially, and it is unknown if stimuli that expensive would have been carried out if the economy was struggling at the time.

Will the COVID-19 Stimuli be successful?

The economic position of Australia prior to the GFC and COVID-19 are quite similar, as the Morrison government was expecting to deliver a surplus for the next budget. However, with COVID-19 placing parts of China into lockdown, this will have a negative affect on Australia’s imports and exports, which will also be largely impacted by Australia itself likely going into a partial or full lockdown in the future.

It is interesting to note that the RBA slashed the cash rate by 4.25% between August 2008 and April 2009 to encourage borrowing and investment. It is highly unlikely a cash rate cut of this magnitude would happen today given the cash rate is currently at a record low of 0.5%, but a cut may be on the horizon. Countries such as Sweden and Denmark have negative interest rates, so it isn’t out of the question that they may be implemented in Australia as well.

Final Comments

Australia were able to rely on China for economic stability during the GFC, however during the COVID-19 pandemic this is not feasible and the Australian government must find a way to overcome the barrier of a significant decrease in international trade. The Morrison government’s stimulus is a step in the right direction, however it is significantly smaller than the stimuli provided by the Rudd government during the GFC, and comes in a situation with less favourable circumstances and more unpredictability. Further stimuli or economic assistance for lower income workers and small businesses will likely be needed in the future, as well as a way to balance the loss of a large amount of international trade, if Australia is to avoid its first recession in almost 30 years.

Very nice Zac! Well structure and a thoughtful piece overall!

LikeLike

I think that Kevin Rudd’s strategy was best! Our government should follow a similar course of action; and I think this will hit our economy much harder than 2008.

LikeLiked by 1 person